Initial Management

Clinical Outline

= Primers in Thyroidology

= Journal Club Presentation

= Case-based Discussion (inc. roundtables)

= Grand Rounds Lectureship

Management Recommendations

1. Preoperative Assessment

A. Patient History & Physical Exam Impacting Operative Risk1

AAES

In anticipation of thyroid surgery, the following history and physical exam findings should be elicited and identified:

- Personal or family history of complications associated with general anesthesia.

- Personal history of general anesthesia challenges due to difficult intubation or limited oral opening.

- Presence of a neck scar or prior neck surgery that includes:

- Carotid procedure,

- Cervical spine surgery,

- Thyroid or Parathyroid procedure

- Any history of either a bleeding or clotting abnormality.

- Medication that affects clotting including antithrombotic or antiplatelet drugs.

- Any preexisting condition that causes chronic diarrhea such as irritable bowel disease (IBD) or Roux en Y gastric bypass.

- Patients who have undergone gastric bypass surgery and are scheduled to undergo either a total thyroidectomy or a completion thyroidectomy, should be advised that they are at increased risk of severe postoperative hypocalcemia.

B. Hypercalcemia2

AAES

- Patients who are diagnosed with hypercalcemia and are scheduled to undergo thyroid surgery should undergo evaluation for hyperparathyroidism

- Concurrent parathyroidectomy should be performed in patients who are undergoing thyroidectomy and are diagnosed with primary hyperparathyroidism

- Patients with familial primary hyperparathyroidism who are scheduled for thyroid surgery should undergo preoperative evaluation for coexisting hyperparathyroidism

C. Imaging for Biopsy Proven or Suspicious Thyroid Nodules

ATA // AAES // NCCN // TIRADS

- Ultrasound of the thyroid and neck including lateral lymph node compartments is recommended for all patients undergoing thyroidectomy for malignant or suspicious nodules. Meticulous documentation of the size, location, and invasion of adjacent structures is important.1,3–5

- Cross-sectional imaging (CT, MRI) with intravenous contrast is recommended for patients with advanced disease, including invasive or symptomatic primary tumors, or clinically apparent multiple or bulky lymph node involvement.1,4

- Fine-needle aspiration of sonographically suspicious lymph nodes is recommended to confirm malignancy if technically feasible and if this would change management.2,3,6

- For patients to be classified as cN1b, only one positive node needs to be documented in the lateral neck.

Advising FNA: Lymph Node Size

TIRADS-ACR vs. ATA

There is some disagreement amid guidelines in advising FNA for suspicious lymph nodes3,6

- ATA suggests FNA of sonographically suspicious lymph nodes if their smaller diameter is ≥ 8–10 mm.3

- TIRADS-ACR recommends FNA biopsy of all suspicious lymph nodes.6

- A suspicious node in the central compartment should be biopsied if technically feasible and if this would change management. An alternative approach is to excise any suspicious central compartment nodes at the time of surgery and obtain frozen section analysis.

- Thyroglobulin washout from suspicious lymph nodes is appropriate in selected patients in addition to cytology, though interpretation may be difficult in patients with an intact thyroid gland.6

- FDG-PET is not recommended in routine imaging for first-line evaluation of most thyroid cancers.5,6

Supplemental Educational Content

Strategies for Overcoming Barriers to Specialty Care for Thyroid Disease and Thyroid Cancer

Presenter: Megan Haymart, MD

- 12:14 — Survey on TSH Suppression

Dr. Haymart discusses how likely endocrinologists and surgeons were to recommend TSH suppression in intermediate-risk, low-risk, and very low risk clinical scenarios. Through multivariate analysis, physicians with higher volume (greater than 40 patients per year) were less likely to suppress TSH in low or very low risk patients. - 16:23 — Physician-patient Interplay

Dr. Haymart presents results from a multivariable, weighted logistic regression that shows how physicians seeing more than 40 thyroid cancer patients/year were associated with less use of radioactive iodine for low-risk thyroid cancer. - 21:46 — Hierarchy of Needs

Dr. Haymart discusses a Maslow’s hierarchy of needs model in regards to thyroid cancer outcomes. She presents different areas we can address to improve care and reduce disparities. - 27:48 — Opportunities for Mobile Health

Dr. Haymart shares the importance and the potential for telemedicine to reduce disparities, particularly in rural settings.

2. Active Surveillance (AS)

A. Intrathyroidal Papillary Thyroid Cancer ≤ 1 cm

ATA // ESMO // JAES // NCCN

- In properly selected patients with low-risk papillary thyroid cancer ≤ 1 cm in maximal dimension (T1a, papillary microcarcinomas) that appears to be confined to the thyroid, an active surveillance (AS) management approach can be considered as an alternative to thyroid surgery. Primary tumors that are located on the posterior surface of the thyroid lobe in proximity to the recurrent laryngeal nerve are not considered ideal candidates for AS.

- Clinical features that would favor surgical intervention rather than active surveillance include:

- Cytology indicating aggressive variant,

- Location of the tumor in a subcapsular location near the recurrent laryngeal nerve or trachea,

- Evidence of metastatic disease,

- Radiation exposure, or extrathyroidal extension,

- Age < 20 years,

- Other surgical disorders of the thyroid or parathyroid in patients with suitable low risk cancers.

- The presence of tumors located on the anterior surface of the thyroid and showing imaging evidence of minimal invasion of the overlying strap muscles represent an area of some controversy in terms of suitability for AS. However, certain guidelines do endorse the safety of AS in this group of patients.

- There is no reliable information to support the safety of AS based on the presence of specific mutations.

- Patients with low-risk thyroid cancers that are deemed to be suitable candidates for AS do not need a chest CT prior to AS but may require one if the disease progresses.

- Multifocal disease, if all lesions meet low risk criteria, is not a contraindication for AS.

- Patients with a family history of thyroid cancer may be suitable candidates for AS.

- Patients with otherwise favorable micropapillary thyroid cancers should not be excluded from AS on the basis of the degree of vascularity of the nodule or the pattern or degree of calcification.

- Patients with coexisting Graves’ Disease and a suitable micropapillary thyroid cancers for monitoring should not be excluded from AS.

- There may be a role for TSH suppression in patients undergoing AS.

Supplemental Educational Content

Invasion of a Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve from Small, Well-Differentiated Papillary Thyroid Cancers

Presenter: Samantha Newman, MD

Dr. Samantha Newman discusses the above article. The success of an active surveillance management approach to low-risk papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) is heavily dependent on proper patient selection. For example, primary tumors located in a subcapsular position immediately adjacent to the trachea or a recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) are considered to be inappropriate for active surveillance. Since preoperative imaging cannot reliably rule out extrathyroidal extension or reveal the full course of the RLN relative to the thyroid gland, it is important for clinicians to understand subcapsular tumor locations and minimum tumor sizes that are most likely to be associated with gross invasion of the RLNs.

- 6:23 Considerations for Active Surveillance

Dr. Samantha Newman discusses factors to be considered when determining whether active surveillance is an option for thyroid cancer patients, noting implications of recurrent laryngeal nerve invasion on this decision. - 21:16 Size & Location

Dr. Samantha Newman presents findings on thyroid tumor size and likelihood of recurrent laryngeal nerve invasion, highlighting their potential implications for guidelines related to active surveillance management. - 41:36 Surgical Considerations for RLN Invasion

Dr. Ricard Simo provides an overview of surgical considerations to be made when confronting potential recurrent laryngeal nerve invasion of thyroid tumors in patients.

Active Surveillance of Adult Low-Risk Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma

Presenter: Iwao Sugitani, MD, PhD

Dr. Iwao Sugitani discusses active surveillance (AS) of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC) in Japan, including its historical background and future perspectives.

- As a result of (AS) for over 2,000 patients with cT1aN0M0 PTMC, the vast majority of tumors did not grow, only a few patients developed lymph node metastases (LNM), and outcomes were not badly affected by delayed surgery.

- Guidelines have acknowledged AS for patients with low-risk PTMC as an attractive alternative to immediate surgery.

- Candidates for AS are adult patients with clinical T1aN0M0 low-risk PTMC.

- AS has merit for multiple PTMCs to avoid total thyroidectomy and resulting surgical complications.

- The criteria for AS might be able to expand to tumors <15 mm.

- There is no evidence regarding how much time must pass before AS can be discontinued. AS throughout life is recommended.

- Evidence for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) regarding management of low-risk PTMC is still insufficient, requiring long-term comparative studies in the future.

Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing: Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma in the US

Presenter: Emad Kandil, MD, MBA, FACS, FACE

Summary

Dr. Emad Kandil presents a retrospective cohort study that explored the presence of high-risk pathological features at presentation with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC) and association of these features with distant metastases.

- Findings demonstrated that more aggressive surgical intervention improved survival for patients with PTMC that had advanced pathological features.

- Dr. Kandil concludes that all patients with PTMC ought to be advised that surgical intervention could serve as a diagnostic and therapeutic approach.

- Dr. Louise Davies notes that factors which are associated with decreased survival can be identified before surgery, and that these factors can be assessed before advising a patient on the best course of action forward.

- Dr. Davies highlights that the fittingness of surveillance should be reassessed at each visit with a patient.

Identifying Risk Factors to Reduce the Need for Thyroidectomies

Presenter: Janice Pasieka, MD

Summary

Dr. Janice Pasieka presents a study on the identification of intraoperative risk factors and their role in reducing the need for completion thyroidectomy in low-risk papillary thyroid cancer patients. Dr. Jeffrey Harris joins as the featured guest discussant and considers the role of lobectomy in low-risk thyroid cancers.

- Traditionally, total thyroidectomy was standard of care for PTC measuring 1 cm or more in size.

- In 2015, the ATA guidelines stated that a total thyroidectomy or lobectomy could be performed for PTC measuring 1-4 cm without any other high-risk features.

- There can be occult high-risk features recognized either operatively or postoperatively in seemingly low-risk patients.

- A challenging question for clinicians: what preoperative factors should be used in order to determine patients suitable for lobectomy to minimize the need for completion thyroidectomy?

- The objective this study was twofold: 1) to identify the prevalence of intraoperative high-risk features and their impact on reducing the need for completion thyroidectomy, and 2) to determine whether varying the preoperative selection criteria for lobectomy could reduce the need for completion thyroidectomy.

- The study found that the prevalence of intraoperative high-risk features was 21%, and that varying the preoperative selection criteria for lobectomy could not reduce the need for completion thyroidectomy.

- Despite careful preoperative assessment, low-risk PTC patients need to be informed that there is a 21% intraoperative conversion rate to total thyroidectomy, and that up to 30% of patients will still require a completion thyroidectomy.

- It remains unclear whether lobectomy should be offered for most low-risk thyroid cancers.

A Quantitative Analysis Examining Patients’ Choice of Active Surveillance or Surgery for Managing Low-Risk Papillary Thyroid Cancer

Presenter: Anna Sawka, MD

- 4:03 Treating PTC with Active Surveillance (AS)

Dr. Sawka defines active surveillance and discusses criteria and recommendations for using active surveillance to treat PTC. - 8:36 How Do Patients Decide on Treatment?

Dr. Sawka discusses the methodology of her longitudinal study and how her team investigated multiple factors that could affect patients’ treatment decisions regarding PTC. - 30:20 Study Limitations

Dr. Sawka discusses study limitations such as validity of questionnaires and potential referral bias. - 34:24 Dr. Elisei’s Presentation

- 38:42 Factors Affecting Disease Progression Under AS

Dr. Elisei highlights findings from multiple studies to explain how PTC disease progression under active surveillance correlates with factors such as age, pregnancy, and anxiety. - 46:20 Is Active Surveillance Safe for PTC Patients?

Dr. Elisei summarizes results from a study she conducted assessing tumor growth over time in patients undergoing active surveillance and discusses final considerations.

B. Frequency & Duration of Ultrasound Studies

ATA // JAES // NCCN

- Active surveillance includes ultrasound evaluations every 6 months for 2 years, followed by annual surveillance.5–7

- It is advisable to continue AS throughout a patient’s life including into more advanced years due to concern for the potential for more aggressive disease to appear in older patients.7

C. Indications to Advise Surgery for Patients

ATA // JAES

- Tumor diameter of:

Tumor Diameter

JAES vs. ATA

- JAES advises surgery for tumors diameters > 15 mm6

- ATA advises surgery for tumors diameters > 13 mm7

- Tumor Growth:

- Increase in the maximal diameter of the nodule by > 3 mm.

- Growth defined as a 20% increase in at least two nodule dimensions and a minimal increase of 2 mm, or a 50% or greater increase in volume.3

- Appearance of new lymph nodes.

- Appearance of other thyroid or parathyroid disease.

- Change in patient preference.

Supplemental Educational Content

Experience with Active Surveillance of Thyroid Low-Risk Carcinoma in a Developing Country

Presenter: DrS. Alvaro Sanabria and Carolina Ferraz

Summary

Dr. Sanabria and Dr. Ferraz present their research that details the usage of Active Surveillance as opposed to immediate surgery in developing countries in Latin America.

- Thyroid cancer incidence is growing, especially for PTC and low-size tumors. However, the mortality rate remains low.

- Overdiagnosis of low-risk thyroid carcinomas increases the potential for unnecessary surgeries.

- The goal of Dr. Sanabria’s study was to present the experience of active surveillance in patients with thyroid nodules classified as Bethesda V-VI in Colombia

- At the first patient visit, it is necessary to moderate the patient’s anxiety regarding the diagnosis, offer information about treatment alternatives, and then make an informed decision (8:46)

- There are certain trends that often influence an individual’s decision to undergo either active surveillance or surgery. Those who are more anxious or are under 40 years old ten to favor surgery. Conversely, those who fear surgery and have the discipline to follow a surveillance schedule and attend long-term follow up more frequently opt for active surveillance (13:58)

- Dr. Sanabria found that 62% of patients had nodules that remained stable or even decreased in size during surveillance.

- With this data, Dr. Sanabria suggests that active surveillance is certainly possible in developing countries, despite major differences in health systems and health care structures. The results were similar to those reported from Japan, USA, and Italy

- Diameter measured in millimeters is a better indicator of nodule growth when compared to volume. This is because the formula for volume can overestimate the biological behavior.

- Dr. Ferraz complemented Dr. Sanabria’s presentation with a discussion on the challenges and prospects of active surveillance for thyroid low-risk carcinoma in Latin America.

- A survey of endocrinologists and head and neck surgeons in Brazil revealed that 23% of 657 sampled doctors preferred active surveillance as their first choice for patients with suspicious nodules under 10mm. Of the 77% who advocated for surgery, 58% specifically recommended total thyroidectomy. Thus, physicians in Brazil still prefer surgery (31:00).

- In the public sector of Brazilian hospitals, providers should take the extra time to explain active surveillance to their patients. A challenge to this is the limited duration of appointments and large patient demand at such hospitals.

- In the private sector, patients tend to have many doctors giving independent recommendations. This undermines the recommendation of the surgeon. Dr. Ferraz concludes with a re-emphasis of Dr. Sanabria’s following suggestions for active surveillance: There must be more multicentric studies for the Latin American population, patients must be properly educated and given more time one-on-one with their doctors, and urgent medical education is needed to convey that active surveillance is both safe and feasible. (37:05)

Barriers to the Adoption of Active Surveillance

Presenter: Dr. Susan Pitt

Summary

Dr. Susan Pitt presents a lecture on barriers to the adoption of active surveillance (AS) in low-risk papillary thyroid cancers.

- There is a lack of information on AS available online. (7:32)

- Barriers to AS for patients include: cancer fear, the assumption that surgery is the default treatment, and the peace of mind that may be associated with the removal of cancer. (11:18)

- Physician-identified barriers to AS include awareness/knowledge, beliefs about cancer and outcomes of AS, self-efficacy, lack of data/protocol availability, malpractice concerns, and disagreement with guidelines. (38:08)

- Many of the barriers to the adoption of AS are adjustable. There is hope that AS can be used more frequently and more effectively in the United States moving forward. (40:32)

3. Surgical Treatment

Supplemental Educational Content

Surgical Management of Thyroid Nodular Disease – Personal Evolution Throughout 4 Decades of Practice

Presenter: Jeremy Freeman, MD, FRCSC, FACS

Using four decades of practice for reference, Dr. Jeremy Freeman presents troublesome areas in the management of differentiated thyroid cancer as well as potential pathways forward.

Summary

Dr. Jeremy Freeman highlights seven troublesome areas in the management of differentiated thyroid cancer:

- Pervasive use of inappropriate ultrasound

- Liberal approach to fine needle aspiration

- More extensive primary surgery than necessary

- Liberal utilization of prophylactic central neck dissection

- Extensive application of RAI

- Aggressive approach to central compartment (and perhaps lateral) recurrence

- Too many surgeons operating on too few cases

Dr. Jeremy Freeman proposes that education and further development of molecular markers can serve as solutions to many of these troublesome areas in the management of differentiated thyroid cancer.

Dr. Mike Tuttle suggests that the shift toward an aggressive paradigm in thyroid cancer management in previous years was likely caused by an increase in technology and a “common sense” line of thinking (if someone has cancer, they want it out”).

Trends in the Management of Localized Papillary Thyroid Cancer in the United States (2000–18)

Presenter: Elisa Pasqual, MD, PhD

Summary

Background: In response to evidence of overdiagnosis and overtreatment of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), the 2009 and 2015 American Thyroid Association (ATA) adult guidelines recommended less extensive surgery (lobectomy vs. total thyroidectomy) and more restricted use of postsurgical radioactive iodine (RAI) in management of PTC at low risk of recurrence. In 2015, active surveillance was suggested as a viable option for some <1-cm PTCs, or microcarcinomas. The 2015 ATA pediatric guidelines similarly shifted toward more restricted use of RAI for low-risk PTCs. The impact of these recommendations on low-risk adult and pediatric PTC management remains unclear, particularly after 2015.

Methods: Using data from 18 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) U.S. registries (2000–2018), we described time trends in reported first-course treatment (total thyroidectomy alone, total thyroidectomy+RAI, lobectomy, no surgery, and other/unknown) for 105,483 patients diagnosed with first primary localized PTC (without nodal/distant metastases), overall and by demographic and tumor characteristics.

- 14:59 Changes In PTC Treatment Over Time

Dr. Elisa Pasqual describes trends in treatment for localized papillary thyroid carcinoma over time by size for tumors ranging from 0–4 cm. - 25:56 Stronger Wording, Stronger Results

Dr. Whitney Goldner reviews study findings which suggest that the use of stronger wording in thyroid guidelines results in greater changes in practice. - 43:50 PTC Treatment Trends: Takeaways and Questions

Dr. Elisa Pasqual discusses take-home messages regarding changes in treatment alongside changes in guidelines for PTC and points to questions for further investigation.

Safety, Efficacy & Feasibility of Outpatient Thyroidectomy

Presenter: Minerva Romero Arenas, MD

- 3:47 Inpatient vs. Outpatient Thyroidectomy

Dr. Arenas provides some background information regarding the shift from inpatient to outpatient thyroidectomy and important considerations such as cost, length of hospital stay, surgical setting, and patient factors. - 14:07 When Is Outpatient Thyroidectomy Appropriate?

Dr. Arenas discusses the impact of clinical practice guidelines on outpatient thyroidectomy. - 17:44 Indications & Contraindications for Outpatient Thyroidectomy

Dr. Arenas goes into an in-depth discussion of what factors are associated with higher complications.

A. Extent of Initial Thyroid Surgery

ATA // ESMO // JAES // NCCN

The appropriate extent of thyroid resection; namely, ipsilateral lobectomy (LT) versus total thyroidectomy (TT) is controversial for low-risk PTC and FTC. Decisions about the extent of thyroidectomy should be individualized and determined in consultation with the patient. Consideration should be given to the fact that TT enables radioactive iodine therapy, enhances post-treatment assessment with serum thyroglobulin and generally has a lower rate of recurrence; however, there is a higher rate of surgical complications including hypoparathyroidism and recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, especially among low-volume surgeons.5–8

Preoperative risk assessment and risk-adapted decision-making for extent of thyroidectomy are crucial. In general, TT is recommended for ATA high-risk cases and LT for ATA low-risk cases.

ATA Low-risk, well-differentiated cancers should meet all the following criteria:

- Primary tumor < 4 cm, no ETE, cN0, cM0.5–8

- The nodal criteria for low-risk thyroid cancers include nodes that are not clinically evident and less than 5 pathologic nodes where all nodes are micrometastases (< 2 mm).5,6

- Unilateral nodules in the thyroid or low-risk appearing nodules in the contralateral lobe,5,6,8

- No prior head and neck radiation exposure,5,6,8

- No family history of thyroid cancer,5,6,8 and

- No aggressive features on cytology.5,6,8

For patients with ATA intermediate-risk tumors (not belonging to the low-risk or high-risk group), either TT or LT can be chosen. Some of the following features may only be known after surgical excision and histologic review.

- ATA Intermediate risk cancers include one or more of the following criteria:5,6

- Minimal extrathyroidal extension.

- Presence of aggressive histologic features including hobnail, tall cell and columnar.

- Evidence of vascular invasion in PTC.

- Clinically evident nodal disease.

- > 5 pathologic lymph nodes all < 3 cm in greatest dimension.

- Multifocal micropapillary thyroid carcinomas with ETE and BRAFv600E mutation.

- Evidence of nodal disease on the first post treatment whole body scan.

Supplemental Educational Content

Marked Decrease Over Time in Conversion Surgery After Active Surveillance of Low-Risk Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma

Presenter: Akira Miyauchi, MD, PhD

Background

During the past 3 decades, the incidence of thyroid cancer increased rapidly in many countries.

- Mostly due to increase in detection of small PTCs

- Papillary microcarcinoma (≤ 1 cm) (PMC) became about 50% of thyroid cancers

However, mortality from thyroid cancer remained stable.

- Many researchers suggested overdiagnosis and overtreatment of small PTCs

Furthermore, studies found latent thyroid cancer (> 3 mm) in 2.3 to 6.4% of people.

- Screening studies with US-FNA found 3.5% of adult Japanese women to have thyroid cancer (Takebe K et al.), yet the prevalence of clinical thyroid cancer was 3.1/100,000

The Hypothesis

Dr. Miyauchi hypothesized that most papillary microcarcinomas would remain small. How could we distinguish between those that will grow and those that will remain small?

- Observation without immediate surgery

- Doing surgery for only those that show slight progression would not be too late

- Immediate surgery for all PMCs might result in more harm than good

Active Surveillance for Low-risk PMC

Dr. Miyauchi proposed a clinical trial of observation without immediate surgery at Kuma Hospital in 1993

- Diagnosis was made with US-guided FNA. (PPV is 98%)

- For high-risk PMCs, surgery was recommended.

- For low-risk PMCs, surgery and observation were proposed. Patients chose.

- Patients who chose observation were followed with US at 6 mo and 12 mo.

- Patients were recommended surgery if tumors showed increase in size by 3 mm or more, or if novel lymph node metastases appeared.

Results

1235 patients, 5% had family history of thyroid cancer, 12% had multiplicity

- At 10 years, 8% of patients showed tumor enlargement by 3 mm or more

- At 10 years, 3.8% of patients showed lymph node metastases

Surprisingly, patients under 40 years of age were more likely to show tumor enlargement and lymph node metastasis than those ≥ 40.

Only young age, and not multiplicity or family history, significantly associated with tumor enlargement.

- Additionally, only young age, and not multiplicity or family history, significantly associated with lymph node metastasis.

- PMC can stop growing after the point of tumor enlargement.

Conclusions

Regardless of the reasons, patients with PMC in the latter part of the active surveillance (AS) study were significantly less likely to undergo conversion surgery than those in the earlier part.

- Likely the accumulation of favorable outcomes with AS significantly contributed to physicians’ confidence and patients’ trust and understanding of the disease

- These changes should be natural when we encounter a new management modality

Extent of Thyroid Surgery in Low Risk Thyroid Cancers

Presenter: Iain Nixon, MD

Extrathyroidal Extension • Complication Rates • Histology

Diagnostic Test Accuracy of Ultrasonography vs Computed Tomography for Papillary Thyroid Cancer Cervical Lymph Node Metastasis

Presenter: Srinivasan Harish, MD

- 1:54 What is the Most Effective Preoperative Imaging Technique?

Dr. Alabousi discusses how different imaging techniques are currently used to evaluate PTC, and how his systematic review compares ultrasound (US) versus CT for preoperative evaluation. - 4:33 Steps for Conducting a Systematic Review

Dr. Alabousi explains the inclusion/exclusion criteria, data extraction methods, and risk of bias assessments used when putting together the systematic review. - 13:58 Highlighting Comparisons Between Studies

Dr. Alabousi summarizes the results of the systematic review, comparing findings for cervical, lateral compartment, and central compartment lymph node metastasis. - 24:42 When to Use CT Along with Ultrasound?

Based on results from the systematic review and previous studies, Dr. Alabousi recommends specific cases where using CT in addition to ultrasound would be beneficial.

B. Indications for Thyroid Lobectomy5,7

JAES // NCCN

- Unilateral nodules in the thyroid, with or without low-risk appearing nodules in the contralateral lobe (for nodules in the contralateral lobe that meet criteria for FNA, FNA is recommended prior to surgery)

- No family history of thyroid cancer

- No aggressive cytologic features

- Follicular neoplasms (Bethesda IV) that lack evidence of invasion or metastatic disease

Supplemental Educational Content

Staged Thyroidectomy

Presenter: Ashok Shaha, MD, FACS

Overtreatment • Complications from Surgery • Evidence-based Medicine

Management of Thyroid Cancer Patients after Lobectomy

Presenter: Jennifer Perkins, MD

- 4:13 — Choosing Surgical Approach Considerations

Dr. Perkins provides an overview of clinical factors that impact the decision of choosing between lobectomy versus total thyroidectomy. - 7:25 — Rising Thyroglobulin Level

Dr. Perkins presents a case of a 68-year-old female with left thyroid nodule noted incidentally on a carotid ultrasound. This patient underwent a left hemi-thyroidectomy and presented with rising thyroglobulin levels five years after surgery. Dr. Perkins presents other studies to examine whether thyroglobulin post-lobectomy is reliable. - 16:30 — Completion Thyroidectomy

Dr. Perkins presents a case of a 35-year-old female with palpable thyroid nodule noted on physical examination. FNA revealed a 1.9 cm papillary thyroid cancer, tall cell variant. Dr. Perkins evaluates whether this patient should receive completion thyroidectomy, and if so, whether this patient should receive radioactive iodine ablation. - 23:36 — Vascular Invasion

Dr. Perkins shares a case of a 54-year-old woman who underwent a right lobectomy. As this patient presented with two vessels of vascular invasion, Dr. Perkins examines the impact of vascular invasion and capsular invasion.

C. Presence of Contralateral Nodules

For nodules in the contralateral lobe that meet criteria for FNA, FNA is recommended prior to surgical intervention.

D. Indications for Total Thyroidectomy

ATA // ESMO // JAES // NCCN

Total thyroidectomy is advisable for patients with tumors displaying ATA high-risk features that include the following:

- Maximal diameter of tumor T > 4 cm.

- Gross extrathyroidal extension (ETE).

- Clinically apparent lymph node metastasis (cN1).

- Certain guidelines limit the high-risk criteria to N1 > 3 cm or N1 with extranodal extension.

- Clinically apparent distant metastasis (cM1).

- Poorly differentiated or aggressive features on cytology.

- Patients with prior head and neck radiation exposure in childhood or adolescence are candidates for TT.

There is a controversy concerning minimal ETE or ETE only to the sternothyroid muscle (T3b).

- Certain guidelines recommend TT for patients with minimal ETE or T3b tumor;8

- Other guidelines do not include T3b tumor in the high-risk group and consider LT to be an appropriate surgical procedure.7

E. Indications for Intraoperative Frozen Section

ATA // AAES

- Frozen section can provide important information regarding the presence of central compartment lymph node metastases in situations where that information will change the surgical procedure.2

- Frozen section may be useful in confirming malignancy where that information will change the surgical procedure; frozen section is most likely to be informative for classic PTC and unlikely to be definitive for either follicular carcinoma or follicular variant of PTC.6

- Frozen section may play a role in confirming the identification of parathyroid tissue.2

Supplemental Educational Content

Lobectomy Compared to Total Thyroidectomy

Presenter: Susana Vargas-Pinto, MD

In this week’s Virtual Journal Club, Dr. Vargas-Pinto and Dr. Shaha reviewed the recent studies comparing outcomes for thyroid lobectomy and total thyroidectomy for low-risk thyroid cancer patients.

Summary

- We were honored to hear from Dr. Susana Vargas-Pinto and Dr. Ashok Shaha during today’s Virtual Journal Club. Dr. Vargas-Pinto is a bilingual hispanic surgeon with an interest in reducing healthcare disparities among latino communities in the United States. She is a member of the National Hispanic Medical Association, the Latino Surgical Society, and the Gold Humanism Honor Society.

- Dr. Shaha is a senior attending surgeon at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. He is a prolific author, with over 600 peer-reviewed articles.

- Due to a lack of prospective data on outcomes, providers have been debating the use of lobectomies versus thyroidectomies for differentiated carcinoma of the thyroid for the past 25 years. Historically, total thyroidectomy has been the standard of care for PTC larger than 1 cm.

- In 2015, the American Thyroid Association stratified well-differentiated thyroid cancer patients based on the risk for recurrence and called for the consideration of lobectomy as an option for initial extent of surgery for patients classified as “low risk.” Following these guidelines, however, the surgical community voiced concern regarding the lack of data supporting inferior local regional control after lobectomy.

- Dr. Vargas-Pinto systematic review of comparative functional outcomes between the two surgical outcomes demonstrated that

- In summary, there was no difference in overall survival between lobectomy and total thyroidectomy for patients diagnosed with low-risk classic papillary thyroid cancer as defined by the 2015 ATA guidelines. Still, lobectomy patients must be advised on the risk of recurrence in the contralateral lobe and develop an active surveillance strategy after the operation.

- Dr. Shaha follows up on this presentation with a discussion of why lobectomies have been a controversial topic among surgeons for the past several years. Ultimately, he emphasizes the importance of avoiding overtreatment when managing thyroid cancer. This, along with the decreasing trend of adjuvant therapy usage, is why lobectomies should be more highly considered among low risk and intermediate risk thyroid cancer patients.

- The complications of thyroid surgery are directly proportional to the extent of the thyroidectomy and inversely proportional to the experience of the operative surgeon.

4. Completion Thyroid Surgery

A. Indications Following Thyroid Lobectomy

ATA // AAES // ESMO // NCCN

- In patients who undergo a lobectomy for either presumed benign or known malignant disease, the final pathology will inform the treatment team as to the biologic aggressiveness of the disease. The decision to perform a completion thyroidectomy should be made when a total thyroidectomy would have been initially advisable if the histologic information was known either preoperatively or intraoperatively.2,6

- Indications for completion thyroidectomy either based on intraoperative findings or after surgery include:

- Tumor > 4 cm.2,5,6

- Identification of distant metastases.5–8

- Gross positive resection margins.5

- Gross extrathyroidal extension including RLN or tracheal involvement.2,5,6

- Macroscopic multifocal disease (> 1 cm).5

- Confirmed nodal metastases except where the nodal disease is incidental (N1A) and there are fewer than 5 pathologically confirmed nodes and none of the nodes is > 5 mm or all nodes are < 2 mm size. 6

- Poorly differentiated thyroid cancer.5

- Confirmed contralateral malignant disease.5

- ATA Intermediate-risk features not included above for which the surgeon should consider a completion thyroidectomy following a thorough discussion with the patient and a multidisciplinary care team:

- Aggressive histology (e.g., tall cell, hobnail variant, columnar cell carcinoma).6

- Papillary thyroid cancer with vascular invasion.5

- Clinical N1 or > 5 pathologic N1 with all involved lymph nodes < 3 cm in largest dimension.7

- Multifocal papillary microcarcinoma with ETE.6

i. Indications for Follicular Carcinoma

ATA // JAES // NCCN

- Minimally invasive follicular carcinoma does not require completion thyroidectomy.6

- Vascular invasion (> 4 vessels) should undergo a total thyroidectomy.5–7

- High risk features for which completion thyroidectomy should be considered include:

- Age > 45 years and size > 4 cm.7

B. Preoperative Evaluation Before Completion Thyroidectomy

AAES // NCCN

- All patients being considered for a completion thyroidectomy should undergo an examination of their larynx to confirm mobility of the vocal cord on the initial side of surgery.2

- Prior to embarking on a completion thyroidectomy, a thorough assessment of the lateral compartments should be performed to determine if there are clinically evident lateral compartment nodes if that assessment had not been performed prior to the initial lobectomy. Biopsy of suspicious central and lateral compartment nodes should be performed.5

- In the patient deemed to be a candidate for a completion thyroidectomy based on initial or final pathology and who experiences an injury to the RLN at the time of the initial surgery, the surgeon may elect to:

- Wait for a reasonable period of time for the vocal cord to recover function.

- Proceed with surgery on the contralateral side following extensive discussions with the patient.2

5. Extent of Lymph Node Surgery

ATA // AAES // ESMO // JAES // NCCN

A. Suspicious or Biopsy-proven Metastatic Central Lymphadenopathy (cN1a)

For Patients WITH cN1a

Therapeutic central neck dissection should be performed for patients with clinically involved central nodes (cN1a).2,5–8

The extent of central compartment lymph node dissection is not specified in most guidelines.

- Patients with biopsy proven central compartment nodes are advised to undergo bilateral central neck dissection as well as a TT. 8

For Patients WITHOUT cN1a

- Controversy exists regarding the indication for prophylactic central neck dissection (ipsilateral or bilateral) for PTC without clinically involved central neck lymph nodes (cN0).8

- For patients with small, intrathyroidal, clinically node-negative PTC and for most follicular cancers, prophylactic central neck dissection is not recommended.5,6

- Prophylactic central-compartment neck dissection may be considered in patients with a history of radiation exposure in childhood or adolescence, family history of thyroid cancer, or if the information will be used to plan further steps in therapy.

Role of Prophylactic Central Neck Dissection

JAES 2020 vs ESMO

Discordant recommendations regarding the role of prophylactic central neck dissection exist.

- For patients with PTC who have advanced primary tumors(large size (T3 or T4), aggressive features on cytology, extrathyroid extension) or clinically involved lateral neck nodes (cN1b), prophylactic central-compartment neck dissection should be considered.5–8

Supplemental Educational Content

Are There Benefits to Prophylactic Central Neck Dissection?

Presenter: Rebecca Sippel, MD

Summary

Dr. Rebecca Sippel presents the findings of a randomized controlled clinical trial which investigates the role of prophylactic central neck dissection in patients with clinically node negative PTC. Dr. Gregory Randolph joins as the featured guest discussant and elaborates on nodal disease as well as potential complications from thyroid surgery.

- The historic standard of treatment for PTC is total thyroidectomy. However, lymph node involvement is common, and imaging often misses microscopic lymph node involvement.

- A question at the heart of the debate of initial management of PTC is whether more surgery decreases the risk of disease recurrence, or if it increases the risk of complications.

- The aim of this study was to evaluate the risks and benefits of prophylactic central neck dissection in patients with clinically N0 PTC.

- The study outcomes included complications, cancer outcomes, and impact on quality of life (QOL).

- Patients with cN0 PTC treated either with total thyroidectomy (TT) or total thyroidectomy + central neck dissection (TT + CND) had similar complication rates after surgery.

- Oncologic outcomes were comparable between the groups at 1 year.

- While the risk of performing a CND were not higher, the benefit of performing a CND was not clinically evident at 1 year.

- The size of nodes matters. Therapeutic neck dissection should be performed for clinically apparent nodal disease, but is not necessary for microscopic nodal disease.

- Surgeons must have an understanding of parathyroid and nerve complications that can result from surgery.

B. Suspicious or Biopsy-proven Metastatic Lateral Lymphadenopathy (cN1b)

For Patients WITH cN1b

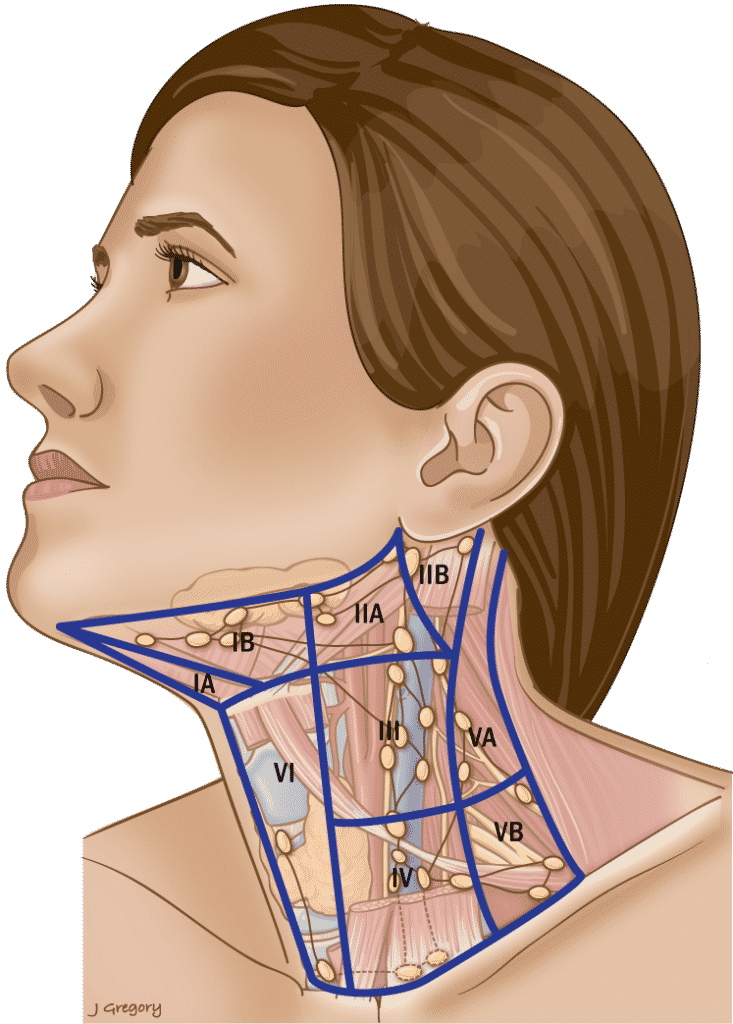

Total thyroidectomy, prophylactic or therapeutic central neck dissection, in addition to therapeutic lateral neck compartment-oriented lymph node dissection (level II, III, IV and VB) should be performed. Prophylactic central neck dissection should be considered due to the high risk of central compartment nodes in patients with lateral compartment nodes.2,5–8

Extended dissection including levels I or VA is only necessary when these levels are clinically involved.5

Table 3. Anatomic Boundaries of the Neck & Involvement in PTC

Level I

| Anterior |

| Anterior belly of the contralateral digastric muscle. |

| Posterior |

| Stylohyoid muscle |

| Superior |

| Body of the mandible |

| Inferior |

| Hyoid |

Triangular boundaries comprising anterior bellies of digastric muscles and hyoid separates IA & IB.

Level II

| Anterior |

| Stylohyoid muscle |

| Posterior |

| Posterior SCM |

| Superior |

| Skull base |

| Inferior |

| Hyoid |

CN XI separates IIA & IIB. IIA nodes lie anterior to IJV.

Level III

| Anterior |

| Sternohyoid muscle |

| Posterior |

| Stylohyoid muscle |

| Superior |

| Hyoid |

| Inferior |

| Horizontal plane defined by the cricoid cartilage. |

Level IV

| Anterior |

| Sternohyoid muscle |

| Posterior |

| Posterior SCM |

| Superior |

| Inferior border of the cricoid cartilage. |

| Inferior |

| Clavicle |

Level V

| Anterior |

| Posterior SCM |

| Posterior |

| Anterior border of trapezius. |

| Superior |

| Convergence of the SCM and trapezius. |

| Inferior |

| Clavicle |

Inferior border of cricoid separates VA & VB.

Level VI

| Anterior |

| Anterior layer of the cervical fascia. |

| Posterior |

| Deep layer of the cervical fascia. |

| Superior |

| Hyoid superiorly |

| Inferior |

| Sternal notch |

Level VII

| Anterior |

| Sternum |

| Posterior |

| Deep layer of the cervical fascia. |

| Superior |

| Sternal notch |

| Inferior |

| Innominate on right and equivalent plane on the left. |

SCM = sternocleidomastoid muscle

Supplemental Educational Content

Prophylactic Central Compartment Neck Dissection Required in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Patients with Clinically Involved Lateral Compartment Lymph Nodes

Presenter: Victoria Harries, MD

Prophylactic Central Neck Dissection • Hypoparathyroidism • Recurrence

No Clear Benefit to Prophylactic Neck Dissection

Presenter: Rebecca Sippel, MD

Dr. Rebecca Sippel presents the conclusions from “A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial: No Clear Benefit to Prophylactic Central Neck Dissection in Patients With Clinically Node Negative Papillary Thyroid Cancer.”

- This study took place at a tertiary care center which may explain why the risk of performing a central neck dissection (CND) was not higher.

- However, benefits of CND could not be proved.

- 20% of patients, in both the control and experimental group, had indeterminate lab or imaging findings at one year

- It is important to follow these patients long term to see how this finding relates to recurrence rates

Location & Cause of Residual Lymph Node Metastasis

Presenters: David Hughes, MD & Dana Hartl, MD

Drs. Hughes and Hartl discuss the risk factors of and causes for missed or residual lymph node disease in central and lateral neck compartments following surgery for differentiated thyroid cancers.

Summary

- This week, we are incredibly excited to welcome Dr. David Hughes and Dr. Dana Hartl. Dr. Hughes is an Associate Professor and Program Director of the Norman W Thompson Endocrine Surgery Fellowship at the University of Michigan. His clinical research is focused on treatment outcomes of patients after endocrine surgery. Following him is Dr. Hartl, joining us from Paris. She is currently Chief of the Thyroid Surgery Unit at Gustave Roussy Institute of Oncology.

- Thyroid cancer is projected to be the fourth most cancer throughout the globe. Thankfully, the mortality rate remains low for all types of differentiated thyroid cancers.

- The particular study he discussed aimed to determine how often residual disease is detected with highly sensitive radioiodine and CT scanning prior to radioiodine therapy but after an initial surgery for differentiated thyroid cancer.

- More importantly, what are the reasons for residual nodal metastases after a primary surgery? Is it due to a lack of detection prior to the surgery, or an incomplete dissection during the surgery?

- The results indicate that patients with residual positive lymph nodes after the surgery were roughly evenly due to a lack of detection before the surgery or a missed lymph node during the surgical dissection. Interestingly, the smaller volume of cancer prior to surgery was less likely to be entirely identified and thus resulted in more frequent postoperative lymph nodes in either the original neck compartment or the lateral neck compartment.

- Dr. Hartl follows up this presentation with her own lecture on the risk factors of lymph node metastases and the treatment of persistent disease after therapeutic neck dissection for thyroid cancer.

- She emphasizes that contrast-enhanced CTs are necessary in the preoperative workup and provide much more valuable information than CT scans without contrast. Contrast enhancement enables providers to distinguish the disease from normal vascular and muscular structures.

- Dr. Hartl also explains her own term – hidden lymph nodes – that refers to lymph nodes that can go undetected because they have metastasized beyond the classic neck levels or reside between neck levels.

6. Perioperative Voice Assessment & Laryngeal Exam

ATA // AAES // NCCN

- Preoperative assessment of a patient’s voice should be undertaken by the treating surgeon as part of the physical exam. Documentation should be performed of both the patient’s and physician’s assessment of voice as well as any recent changes.

- An assessment of the larynx by any of a number of modalities should be carried out (ultrasound, mirror indirect or fiberoptic laryngoscopy) in all patients who meet the following criteria:1,5,6

- Preoperative voice changes or complaints.

- Prior surgery involving the neck or mediastinum that is in proximity to the recurrent laryngeal or vagal nerves.

- Evidence or suspicion of locally invasive cancer.

- The presence of extensive central compartment nodal disease.

- Postoperative voice assessment should be performed in all cases, including a formal laryngeal examination of those patients who are identified as having a persistent postoperative voice abnormality.1

A. Neuromonitoring1

While performing thyroid surgery, the surgeon should make every effort to preserve the recurrent and the superior laryngeal nerves. Direct visual identification of the RLN and its branches is imperative in all cases.

Supplemental Educational Content

Intraoperative Neural Monitoring

Presenters: Joseph Scharpf, MD

Summary

Dr. Joseph Scharpf outlines the underutilized technique of actively monitoring local neural activity during thyroid and neck surgeries. Doing so has been associated with numerous benefits that can ultimately improve surgical success and patient outcomes.

- In this week’s Virtual Journal Club, we are honored to welcome Dr. Joseph Scharf, Director of Head and Neck Endocrine Surgery and Professor of Otolaryngology at the Cleveland Clinic, Lerner College of Medicine.

- Dr. Scharpf is an expert in thyroidology and will be speaking about nerve monitoring during surgery and its implications for patient management. This information can be used to optimize thyroid surgical outcomes specifically, but is vitally important to all specialties!

- The neural monitoring tube used during a procedure produces electromyography (EMG) data that indicates whether or not the nerve is conducting electricity at a health level.

- Intraoperative neural monitoring prevents critical nerves in the neck from being damaged by accidental transection, cauterization, compression, or stretching during an operation.

- Nerve monitoring can even help preserve nerves that otherwise would have had to be sacrificed in more complex surgeries. Conversely, the same monitoring technique can also reveal nerves that are infiltrated with cancer and should be removed even though they appeared healthy upon first appearance.

- Among the many benefits of intraoperative neural monitoring are improved paralysis rates for younger surgeons that may have the same level of experience as more senior surgeons.

B. Parathyroid Gland Management During Surgery1

While performing thyroid surgery, the parathyroid glands and their vascular supply should be preserved. Dissection should be performed along the thyroid capsule to help preserve the parathyroid glands. The vitality of the mobilized glands should be assessed at the completion of the procedure and consideration should be given to parathyroid autotransplantation of any parathyroid where viability is uncertain.

Supplemental Educational Content

Parathyroid Fluorescence

Presenter: Gregory Randolph, MD, FACS, FACE

Near-infrared Autofluorescence • Thyroidectomy • Parathyroidectomy

7. Initial Evaluation of Invasive Thyroid Cancer

AAES // AHNS

- Invasive thyroid cancer that affects the upper aerodigestive tract (UADT) structures including the larynx, trachea and esophagus, should be removed when technically feasible based on histology, disease extent, age, comorbid conditions, the presence of distant metastases (M1), and patient motivation.2

- The extent of surgical resection is best guided by the degree of UADT invasion with a range of techniques employed to remove all gross disease and preserve or restore function.2

- Preoperative histologic assessment is very important to surgical decision making and open incisional biopsy may be necessary in patients with suspicion of anaplastic thyroid cancer or primary thyroid lymphoma.1

- Preoperative examination of the larynx is advisable in the management of invasive thyroid cancer and the preferred method is fiberoptic laryngoscopy.2

- Aggressive thyroid disease should ideally be managed in a multidisciplinary setting.2

Supplemental Educational Content

Management of Invasive Thyroid Cancer

Presenter: Mark Urken, MD, FACS, FACE

Invasive Thyroid Cancer • T4 • Differentiated Thyroid Cancer

A. RLN Management2

AHNS // JAES

- Management of the RLN in patients with invasive thyroid cancer (TC) should be based on the following guidelines:7

- Resection of the encased RLN should be performed if ipsilateral paresis or paralysis is identified on preoperative examination.

- Encasement or minimal adherence of the RLN in the presence of bilateral normal vocal cord mobility should be managed by shaving of the tumor off the RLN provided that all gross disease is removed.7

- If the RLN is encased by tumor and the contralateral vocal cord shows impaired mobility on preop exam, then the encased RLN should be spared by shaving disease off that RLN in an effort to avoid a tracheostomy.

Following sparing of an encased RLN, adjuvant therapy should be considered.

- Confirmation of the histology of the tumor involving an RLN is essential prior to nerve sacrifice which should be avoided in the setting of lymphoma and benign disease.

- If the circumstances permit, based on the proximity to the cricothyroid joint of the point of sacrifice of an involved RLN, a reinnervation procedure should be performed in the primary setting.7

- Intraoperative neuromonitoring may play a very important role in the management of invasive thyroid cancer by providing important information regarding the functional status of the RLN both during and at the completion of the procedure.

- Intraoperative neuromonitoring should be strongly considered in the management of invasive thyroid cancer especially when preoperative vocal cord dysfunction is identified.

- Neuromonitoring may be helpful with intraoperative decisions regarding:

- The decision to proceed to the contralateral side of the thyroid.

- The decision to sacrifice an encased RLN.

- The need for a tracheostomy.

Supplemental Educational Content

Invasion of a Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve from Small, Well-Differentiated Papillary Thyroid Cancers

Presenter: Samantha Newman, MD

Summary

Dr. Samantha Newman presents findings from an analysis of thyroid subcapsular locations associated with risk of recurrent laryngeal nerve invasion, and Dr. Ricard Simo discusses the surgical implications of possible recurrent laryngeal nerve invasion.

- Dr. Samantha Newman emphasizes that there are a series of factors to consider when determining whether a thyroid cancer patient is a good candidate for an active surveillance management strategy, one of which is tumor location in relation to the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

- Dr. Samantha Newman presents a retrospective review of 30 patients with small tumors (< 2 cm) and gross extrathyroidal extension involving the right or left recurrent laryngeal nerve.

- All analyzed tumors which met the above criteria were found in three locations: right paratracheal region, left paratracheal region, and the right lateral posterior region.

- Preoperative radiology studies and clinical findings were not predictive of nerve involvement at the time of surgery.

- Dr. Ricardo Simo discusses surgical considerations to be made when addressing potential recurrent laryngeal nerve invasion of thyroid cancers: consent, preoperative planning, intraoperative findings, surgical technique, central compartment lymph node dissection, and recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) immediate reconstruction.

Varied RLN Course and Increased Risk of Nerve Dysfunction During Thyroidectomy

Presenter: Whitney Liddy, MD & Allen Ho, MD

Summary

RLN anatomy is unpredictably diverse. Classification of its branching subtypes may help avert nerve injury and voice dysfunction. Intermittent and continuous nerve monitoring technologies are complementary but cannot prevent injury due to sudden movement.

Dr. Liddy

RLN injury is an issue because it can lead to permanent or temporary vocal cord paralysis. However, there are 20–30% of patients who don’t complain of hoarseness, so you miss patients who have more subtle voice paralysis. Overall, this is an under-recognized issue. You should visualize the RLN during thyroidectomy to prevent injury. This is a great idea but not foolproof.

The rate of vocal cord paralysis is proportional to the rate of post-thyroidectomy laryngeal exams.

The Study: Large international database study – international nerve monitoring group. (INMSG). The database is ongoing, to look at 5000 nerves at risk.

- Better understand detailed surgical rln anatomic variability.

- Establish correlates between intraop RLN anatomy and electrophysiologic responses.

- Use of information to help minimize complications and ensure accurate and safe intraoperative neuromonitoring.

- Inclusion criteria = all monitored thyroid surgeries following standardized procedures.

- Exclusion criteria = bulky lymphadenopathy, IONM failure, failure to identify RLNs.

- Demographic data

- Anatomic classification of RLN

- IONM + L1 + V1 + R1 + R2 + V2 + L2

- Loss of signal

- Evaluation of type/mechanism of nerve injury and functional outcome

The International RLN Anatomic Classification System

Included in the system is estimated prevalence of each trajectory and othe important neuroanatomic features. Break down to see trajectory by class of laryngeal nerve. Also potentially clinical relevant aspects of the nerve, depending on a list of characteristics. This also includes dynamic nerve characteristics (Type 1 [local], or Type 2 [global]).

Compared study data (observed SAR data) to values in the literature. More nerves than expected followed an abnormal trajectory (23%). Also an increased percentage of nerves that were fixed to the thyroid capsule at 30%.

Types of injuries to the nerve: Traction for nerve at ligament of Berry (highest risk), traction at goiter adhesion, trauma, constriction, thermal, transection injuries

Themes of higher risk: Associated increased risk of injury with nerve invaded by cancer, abnormal neural trajectory, or entrapment of ligament of Berry, lateral lymph node dissection, higher BMI.

More extensive surgery and greater extent of RLN dissection increased risk of neural injury. Most nerve injuries were traction injuries, either at the Ligament of Berry or fixation to the capsule. Nerve mapping with intraoperative neuromonitoring was helpful for prognostication and mapping of neural trajectory and delineation of neural injury. Post-op laryngeal exam allows for predicting neural outcomes more accurately.

Dr. Ho

Nerves in the RLN area at the ligament of Berry, specifically, can cause stress to surgeons in OR. have to balance nerve preservation, and to get to that nerve you have to do some form of “traction.” don’t want to leave too much tissue behind, but also want to not damage the nerve. UChicago study showed major disconnect because patients feel their side effects aren’t being taken seriously by doctors. This translates to how delicate, fragile, or fickle the RLN is.

Critical to understand normal RLN trajectory: For nerve identification, central neck dissection, protecting RLN (critical to procedure). Nerve monitoring should be used as a tool, not a crutch. It lowers the incidence of nerve injury and aids in nerve dissection.

Troubleshooting the NIM tube: Hard to troubleshoot. If the nerve doesn’t work, you cannot tell if the NIM tube has lost contact with the vocal cord. Only an electro-check will show this.

Intermittent nerve monitoring: Provides diagnosis, classification, prevention of nerve injury thru early nerve identification.

Continuous nerve monitoring: Provides real-time info on nerve functional integrity and may prevent some types of nerve injury but cannot assist in nerve localization. Rates of paralysis are similar, but the nerve monitoring arm led to much shorter OR times.

Favors nerve preservation: Young patients w/ conventional PTC, iodine-avid disease, elderly, contralateral vocal cord paralysis.

Favors nerve sacrifice: Aggressive histopathologic sacrifice, iodine-refractory disease, previous external beam RT, normal contralateral vocal cord function, no distant metastatic disease.

Subtypes of thyroid cancer and recurrence: Some are very aggressive, others are not so bad. Investigated in terms of disease survival. When you adjust for confounders, some diffuse sclerosing types are not as bad as regular thyroid cancer. For all others, each subtype carries a greater mortality risk than WDPTC. Malpractice concerns w/ thyroidectomy: Use of IONM, adequacy of postoperative monitoring, adequacy of consent.

Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Invasion by Thyroid Cancer: Laryngeal Function and Survival Outcomes

Presenter: Jennifer Brooks, MD

Summary

- 8:20 — Decision to Resect Nerve

Dr. Brooks discusses how the extent of nerve invasion affects the decision to resect the nerve. She discusses that this decision is largely dependent on the type – Type A or Type B. - 9:30 — Survival Outcomes Data & RAI

Dr. Brooks discusses findings for papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma. Use of RAI was the only statistically significant parameter associated with improved survival. Status of the resection of invaded nerve was not significantly associated with improved survival. - 11:28 — Findings & Future Considerations

Dr. Brooks discusses the prognostic importance of RLN invasion, the importance of RAI, and recommendations for preoperative laryngoscopy. - 22:58 — Dr. Hartl Discusses the Study by Hotoni et al.

Dr. Hartl emphasizes division of their cohort into patients with Ex 2 and Ex 3 to compare data. She discusses that there was a statistically significant difference between recurrence at resection site between groups, but not between rates of distant metastasis and disease free survival. - 37:20 — Considering the Length of Follow-up

…and recurrence rates based on the extent of resection. - 42:30 — Staging Nuances

Dr. Hartl discusses the nuance in staging nerve involvement and notes that the way she stages tumors differs depending on the extent of nerve resection. - 45:40 — Intraoperative Nerve Monitoring

Discussing how intraoperative nerve monitoring affects decisions regarding nerve dissection. If the signal goes out, should this be a deciding factor regarding nerve dissection? Evidence is conflicted, but Dr. Brooks and Dr. Hartl say no since many nerves recover. - 49:00 — Communication with Pathologist

Dr. Hartl discusses how she typically communicates nerve invasion to the pathologist in her own practice and how she records it in the medical record. - 50:50 — Unpacking Preoperative Laryngoscopy

Dr. Brooks further unpacks the recommendation for preoperative laryngoscopy.

B. Tracheal Invasion

ATA // AHNS // JAES

- Tracheal resection should be performed when thyroid cancer is identified as invading the tracheal wall.

- A variety of factors should be accounted for including:7

- Disease stage.

- Degree of disease spread.

- Risk of surgical complications.

- Overall prognosis.

- Impact on quality of life.

- Patient or caregivers’ wishes.

- Skill of the surgical team.

- If there is suspicion of laryngotracheal invasion based on physical exam, patient symptoms or documented presence of distant disease, then cross sectional imaging (CT, MRI) should be performed to provide more detailed information than can be obtained by US examination.2,6

- In the setting of a high suspicion of laryngotracheal invasion, the surgical team should perform a bronchoscopy prior to or at the time of the ablative procedure. The surgical team should be prepared to perform a laryngotracheal resection and reconstruction at the time of the initial surgical procedure.2

- Surgical management of the laryngotracheal complex is guided by the following basic tenets:2

- If a short segment of the laryngotrachea is found to have minimal cartilage invasion, then a shave excision is justified.

- If preoperative or intraoperative determination of intraluminal invasion is identified then a sleeve resection and primary repair should be performed (based on imaging, preoperative endoscopy, or surgical findings).

- If the surgeon performing the thyroidectomy does not have the skills or the experience to perform laryngotracheal ablative and reconstructive surgery then a head and neck or thoracic surgeon with expertise should be available. If neither of these conditions can be met then the surgeon performing the thyroidectomy should close the surgical wound and consider referral to a tertiary center where these skill sets are available.

C. Laryngeal Invasion

AHNS

- The following are basic tenets of laryngeal management when involved by invasive thyroid cancer:

- Shave excision of gross disease involving a partial thickness of the laryngeal framework should be performed when feasible.2

- Partial or total laryngectomy should be performed in cases with gross invasion of the larynx and involvement of the endolarynx.2

- If the surgeon performing the thyroidectomy is not experienced or skilled in partial or total laryngectomy, that expertise should be sought locally or referral to a medical center where that expertise is available.2

D. Esophageal Invasion2

AHNS

Management of the esophagus when involved by invasive thyroid cancer should adhere to the following basic tenets:

- Resection of the esophageal muscularis can be performed without creating a through and through defect when intraluminal invasion is not present.

- A through and through resection of the esophageal wall should be performed when transmural invasion is present.

- Reconstruction of a full thickness defect of the esophagus should be performed by primary repair for smaller defects or with regional or free tissue transfer in the case of larger defects.

E. Vascular Invasion: Workup & Management2

AHNS

- When vascular invasion is suspected or identified by imaging then appropriate workup with imaging is required to determine whether the tumor is resectable.

- CT angiogram and/or MR angiogram should be used to provide information regarding the safety of vascular control and resectability.

- Preoperative assessment to the adequacy of collateral intracranial blood flow and the detailed anatomy of the Circle of Willis should be determined and balloon test occlusion should be considered in order to determine whether carotid shunting is needed during carotid resection and reconstruction.

- One internal jugular vein can be safely resected and flow not restored if the contralateral jugular vein is patent.

- In the event that both jugular veins must be resected, a staged procedure should be performed or reconstitution of flow in at least one vein should be established.

- Partial resection of the vessel wall can be performed for focal invasion and vascular reconstruction with a patch performed when amenable.

8. Key Elements of Communication6

ATA

A summary of the key elements that will likely have a major impact on the peri-operative risk assessment of patients with WDTC and should be communicated clearly to all members of the multidisciplinary team. Many of these elements may influence decision-making in regard to the role of future surgery, the need for and planning of radioactive iodine and other treatment modalities.

A. Preoperative Evaluation for Well-differentiated Thyroid Cancer5–8

ATA // ESMO // JAES // NCCN

- A careful history and physical examination that includes a previous history of head and neck radiation and clinical features of local invasiveness including vocal cord function.

- An anatomical assessment of the primary tumor with ultrasound and/or cross-sectional imaging, looking for features of invasiveness, extent of local and regional disease, and lymph node mapping of the regional basin.

B. Intra-operative Evaluation & Prognostic Indicators6

ATA // ESMO // JAES // NCCN

Convey the following to the multidisciplinary team.

- The presence of gross tumor invasion into the surrounding muscles, trachea, esophagus or soft tissue.

- The extent of the surgical resection either R0, R1 and a detailed description of the gross residual disease left behind.

- Documentation of any normal residual thyroid tissue left to protect the recurrent laryngeal nerve and/or parathyroid glands.

- The extent and the compartments of any lymph node dissection.

- The status of the recurrent laryngeal nerve(s).

- The viability and status of the parathyroid glands.

- The utilization of a standardized narrative or synoptic operative report is recommended to ensure all these elements are clearly documented and articulated.

- Although implied but not clearly articulated, gross residual disease is an important element for the stratification of postoperative treatment modalities.5–8

C. Post-operative Risk Stratification & Ongoing Management

ATA // ESMO // NCCN

- An optimized standardized pathology report required for AJCC/UICC thyroid cancer staging.5,6,8

- Postoperative complications including hypoparathyroidism, RLN function, chyle leak, Horner’s syndrome. These complications should be documented and communicated due to their importance in influencing further treatment and recommendations for completion thyroidectomy, re-operative surgery and timing of any adjunct therapies.5–7

- Postoperative ultrasound documenting thyroid bed remnant, the presence of any residual disease as well as a detailed lymph node mapping should be standardized.8

- The addition of a neck ultrasound should be utilized on postoperative patients to aid with risk-stratification.5,6,8

Supplemental Educational Content

Thyroid Cancer Terminology and Treatment

Presenter: Brooke Nickel, PhD

Summary

Dr. Brooke Nickel discussed the importance of language in thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment decision-making, as well as the effects of these decisions on patients’ quality of life.

Dr. Nickel presented findings from 3 studies related to impacts associated with papillary thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment decision-making:

- Clinicians may underestimate the quality of life implications associated with surgery.

- Patients often feel that they lack full information about their choices and the long-term effects of treatment.

- Quality of Life issues related to diagnosis and treatment span physical, psychological, and lifestyle realms for patients.

Three studies described by Dr. Nickel elucidate the implications of terminology in thyroid cancer care:

- When medicalized language is used, patients exhibit greater preference for more invasive treatment options. The word ‘cancer’ has a major impact.

Dr. Brooke Nickel explains her findings from two qualitative studies with the public (one focus group and one citizen’s jury) on low-risk thyroid cancers:

- The public hopes for more comprehensive community education and health systems reforms to decrease consequences of overtreatment.

- The public expects clinicians and researchers to arrive at agreement on clinical guidelines to facilitate better uptake of active surveillance.

It is important to focus resources on those who really need them.

Language matters in thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment!

Add Upcoming TIROxMDS Seminars to Your Calendar

In 2 quick steps, you can add our entire schedule of upcoming seminars to your calendar today! Then you will get notified of upcoming lectures, presentations and case-based studies. Every Friday at 8:00 AM EST, we cover a new topic from published research.

Add to CalendarReferences

- 1.Patel K, Yip L, Lubitz C, et al. Executive Summary of the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons Guidelines for the Definitive Surgical Management of Thyroid Disease in Adults. Ann Surg. 2020;271(3):399-410. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003735

- 2.Shindo ML, Caruana SM, Kandil E, et al. Management of invasive well-differentiated thyroid cancer: An American head and neck society consensus statement: AHNS consensus statement. Head Neck. Published online August 2014:n/a-n/a. doi:10.1002/hed.23619

- 3.Tessler FN, Middleton WD, Grant EG, et al. ACR Thyroid Imaging, Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS): White Paper of the ACR TI-RADS Committee. Journal of the American College of Radiology. Published online May 2017:587-595. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2017.01.046

- 4.Carty S, Doherty G, Inabnet W, et al. American Thyroid Association statement on the essential elements of interdisciplinary communication of perioperative information for patients undergoing thyroid cancer surgery. Thyroid. 2012;22(4):395-399. doi:10.1089/thy.2011.0423

- 5.Haddad RI, Nasr C, Bischoff L, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Thyroid Carcinoma, Version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. Published online December 2018:1429-1440. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2018.0089

- 6.Haugen B, Alexander E, Bible K, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1-133. doi:10.1089/thy.2015.0020

- 7.Ito Y, Onoda N, Okamoto T. The revised clinical practice guidelines on the management of thyroid tumors by the Japan Associations of Endocrine Surgeons: Core questions and recommendations for treatments of thyroid cancer. Endocr J. Published online 2020:669-717. doi:10.1507/endocrj.ej20-0025

- 8.Filetti S, Durante C, Hartl D, et al. Thyroid cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(12):1856-1883. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdz400